Preserving Things the Way They Came to Us

by Stephen Hale

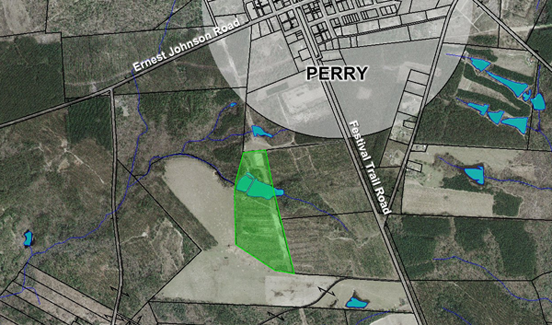

To preserve land that had been passed down to him through many generations, over 272 years, Wade and his wife Sissy Brodie have placed a conservation easement on 39 acres they hold near Perry, SC.

“My mom was a Salley and the land came to me from that branch of the family,” said Wade as he drove his 1991 Ford pickup over back roads that few people know exist.

Part of a land grant to the Salley family from King George, II, in 1736, the original plot was 150. But the Salley family got thousands of acres of land grants in what was then termed the Orangeburg Township. One of those was a sizeable grant from the State of South Carolina in 1798 conferred by Governor Charles Pinckney, a signer of the U.S. Constitution.

On his father’s side the Brodie family has had large landholdings in the same general area for almost that long. “Brodie land” has stretched from Kitchings Mill to Salley since the early 1800s. They came into the country at Charleston and began a logging business along the Edisto River, finally settling in Kitchings Mill.

“The Brodies and the Salleys have been neighbors for over 200 years,” he says with a sense of history. Today Wade is Chairman of the Aiken Corporation and is the retired president of Aiken County National Bank, now Carolina First at Park and Chesterfield. If it’s happening in downtown Aiken, Wade is likely involved. But during deer season he excuses himself from board meetings to be out on his deer stand by dusk.

Preserved for the Future

The conservation easement covers all 39 acres Wade inherited from his mother, 25 in longleaf pine, three ponds that take up six acres and the other eight acres are open land where Wade plants vegetables.

Among the stipulations on the easement is that no building may be erected on the land other than the right of future owners to rebuild a small fishing cabin in its same footprint. One substantial reason for placing a conservation easement on property is the tax deduction. Assessed at $130,000 before the easement, the land lost $51,000 in value because it cannot be developed, and the Brodies reaped that lost amount as a tax deduction.

“We could have left some part of it to build a house on later but we elected not to do that,” said Wade as he walked along his catfish pond. “It can be farmed, future owners can harvest the trees and you can hunt on it, but it is to be left essentially as it is found. I, or future owners can sell it, but the easement goes with it.”

“We have considered giving it to the county or to the town of Perry or some other government agency to use it as a park,” said Wade. Giving it away would mean a second tax deduction, but not as much as the first one.

“Our interest was to preserve it the way it came to us,” he said, looking around at the property that is so much a part of his life. “My family has farmed here for many generations.”

As they have for decades, Sissy and Wade use the land mostly to entertain friends. Renowned as host and hostess, their lucky guests feast on just-netted catfish, freshly harvested deer and the fresh vegetables and scuppernong grapes that Wade grows just yards away from the tiny cabin. “We’ve fed thousands of people down here over the years,” he said smiling.

“I just wanted to keep it the way it came to me,” he said with his always down-to-earth smile. “It came down through my family in good times and bad. It came through the depression, and somebody could have sold it then for some money. So I just wanted to preserve it so other people can enjoy it the way I have.